I can’t believe it is over three decades since we travelled up and down the Karakoram Highway between Pakistan and China, one of the most spectacular and dangerous roads in the world. So what was it like riding along this historic route 35 years ago, a mere six years after it opened and only two years since tourists had been allowed on it? This blog is based on my travel-diary entries during our trip in September/October 1988.

Sunday 25 September. Horribly early start for the 6:45am flight to Gilgit from Rawalpindi/Islamabad. A spectacular ride, but we get the naff seats in the Fokker Friendship aircraft – window almost behind our seats, so have to crane our necks to see the snow-covered peaks, including Nanga Parbat, the ninth highest mountain in the world. As we fly north, the green of the plains gives way to brown and grey of rock, gravel and shale, with tiny patches of cultivation in valley bottoms. The rivers scythe down through the rock.

Gilgit is a pleasant little town, and despite its elevation is surprisingly hot in the sun. We are at the Chinar Inn, the PTDC (Pakistan’s tourist office) place. Saeed (a Pakistani friend we’d met on a visit the previous year) has given us a note for the PTDC office, asking them to give us any help we need. We discover we could have got a minibus up to Sust today, we had enough time. But too late now. In retrospect, I’m glad we got to see Gilgit.

The town is spread out along the highway, and the Chinar is on the outskirts. Mostly single-storey houses and shops, many of mud/brick within a walled courtyard and just one door leading into the courtyard; no windows on the world. We eat at the Chinar; a reasonable buffet of curry dishes, rice, dal, chapati, veg and salad, followed by – er – trifle. The place was full, including a big table of young and elderly Hooray Henrys and Henriettas (for non-Brits, that means posh, rich peope); perhaps that’s why there’s trifle. However, the night did not end happily for me, as something at dinner or earlier in the day gave me stomach cramps and numerous trips to the hotel bathroom, and little sleep.

Majestic mountains

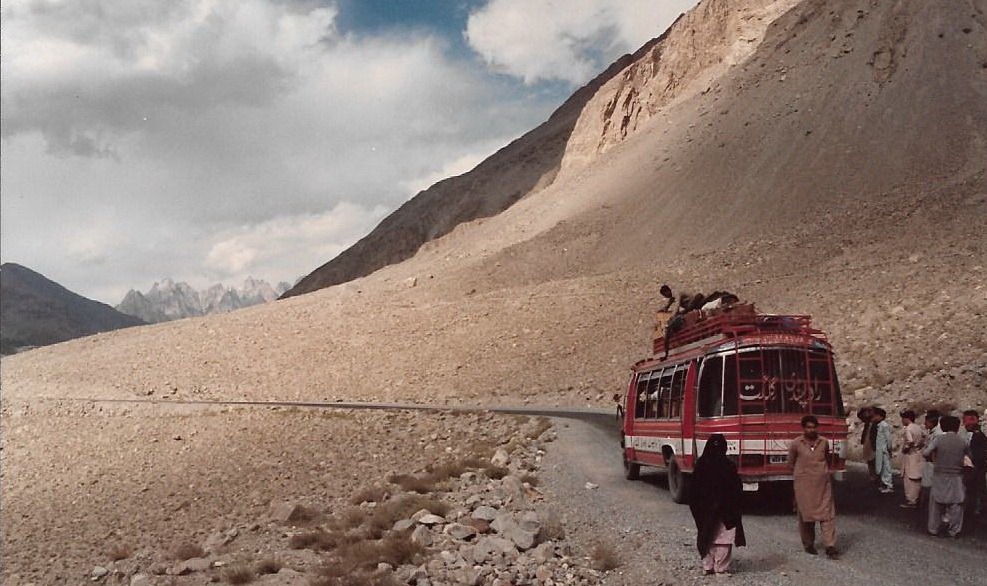

Monday 26 September. The cramps and runs have subsided, which is just as well given the long journey ahead. From Gilgit to Kashgar in China is about 665km, and it will take us the best part of three days. I didn’t feel great. We had decided the day before to forego the minibus and get a Natco (Pakistan government-run service) bus – the start was later and it was 10 rupees cheaper (what were we thinking?). Wish now we had the more comfortable ride in a minibus. The Natco seats are small and have little leg room. C found it particularly hard-going.

The landscape makes up for it though. My diary records it as “awesome”, and before this word got used for anything from a handbag to an Instagram pic of your dinner it was spot on. Let’s just say, it is majestic. The road runs alongside the river in the valley. Huge slabs of rock, scree covered at the bottom, rise almost sheer on either side. Colours are browns and greys; a lot of sand, gravel, shale and boulders, There is frequent evidence of landslips. Despite all this, the road surface is relatively smooth and straight – the river seems to have cut straight down through the rock with little meandering. Maize, apples, potatoes, onions, tomatoes, melons and cabbage are grown in stony fields. Older houses are mud-brick or stone, new ones concrete.

It takes about seven-and-a-half hours to Sust [though more often now spelt Sost], including a scheduled stop for lunch at Aliabad and two unscheduled stops; one where a bulldozer is clearing the road after a landslip and another to repair a puncture. Landslides are permanent hazard of travelling along the Karakoram Highway – and were responsible for a high proportion of deaths among the workers who built the road.

Most of the passengers are Pakistani traders. There are about a dozen non-Pakistanis on board, but most get off at Karimabad to stay in the picturesque Hunza valley. One fellow traveller is accompanied by two policeman and manacled by the wrist to one of them. We learn he is Iranian but has no passport; he’d spent three years in India and one-and-half-years in Pakistan. My diary does not record where he was being taken.

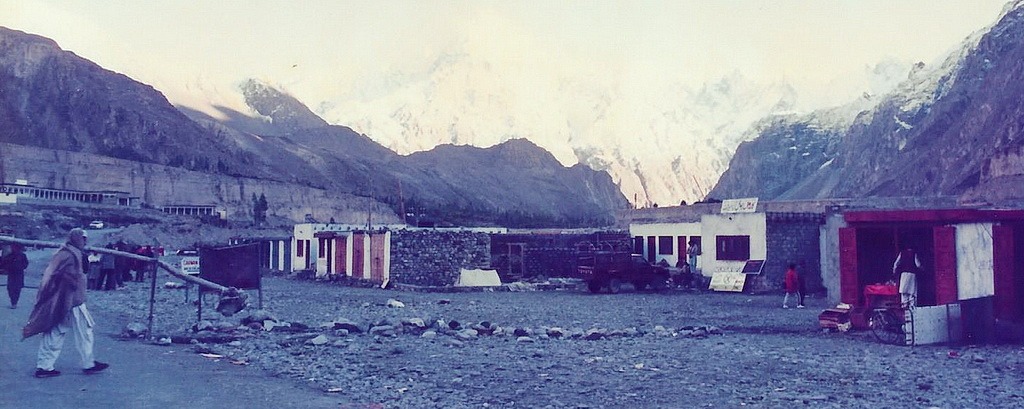

Sust is new, built because of the Karakoram Highway, and has a frontier town feel to it. Facilities mainly consist of basic hotels and food stalls for travellers, built around the Pakistan customs house. We are staying at the Mountain Retreat, which has dorm-type rooms; we negotiate for a room with four beds just for the two of us – it costs 100 rupees (25 per bed) but we have to share a squat loo. We eat in a restaurant in the village with three others from our bus – an American woman and a Norwegian couple – and a Czech guy who is living up in the mountains doing research into marmots and is “on holiday” for four days in the, err, bright lights of Sust. Now, my diary records that he was researching marmosets, but I must have that wrong. There is a Himalayan marmot, and north-eastern Pakistan is one of its habitats.

Tuesday 27 September. We have a short ride in a Landcruiser (190 rupees, organised by PTDC) with the Norwegians and American and a handful of Pakistani men to the customs post where our passports are stamped. The road goes through gorges, studded with tall, slender trees with red, gold, russet leaves. Men driving herds of sheep and goats. The river is clear and the water a brilliant turquoise. The road starts to climb up to the Khunjerab Pass. At the top there’s a sweeping panorama over the flat upland with snowy peaks in the background. Although the sun is shining, it is cold, with a biting wind. The altitude – 4,706m/15,439ft – gives me a slight headache and we are all a bit short of breath.

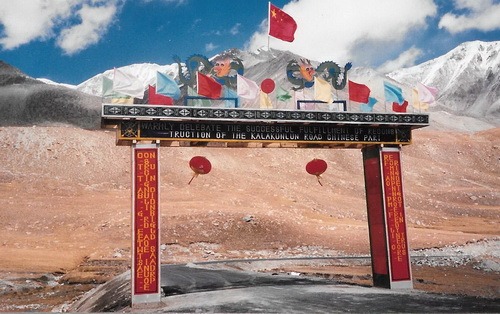

Trading still going strong

There is an archway proclaiming the efforts of the road builders; on the other side is China, making this the world’s highest border crossing. From here we ride down to Pirali, the Chinese customs post. Much filling in of forms. Our bags were not even given a glance, but the Pakistanis with us had their luggage thoroughly searched. We then realise that several of them are wearing many layers of clothing – not against the cold, but because they are smuggling them into the People’s Republic to sell and don’t want to declare them.

We leave the comfortable Land Cruiser and are shown the bus that will take us to Tashkurgan – eventually. We hang around for five hours before we finally get going! There are by now two full bus loads – the Chinese authorities are “collecting” passengers from various Pakistani buses and private vehicles. The scenery is different on this side of the border. The road is straighter, the valley much wider and flatter. Mud-brick houses abound, enclosed by a wall forming a courtyard. Newly cut wheat is piled on the roof tops. The sun is setting, smoke drifts up from the compounds. Locals are finishing their chores in the fields, driving their goats back to shelters. Two-humped camels graze alongside horses and donkeys. I spot one man atop his horse coming through the fields. Black craggy peaks, with the occasional flank of snow, are silhouetted against the ice blue of the western sky.

It is dark by the time we get to Tashkurgan. Our bus pulls into a compound and we are shown our room – a huge space filled with rows and rows of beds and nothing else. It is for the entire bus load of us. There’s no loo, and no food. And there appears to be no choice. There is a mad scramble for the best positioned beds, and we foreigners commandeer a corner of the room for ourselves. The Norwegian couple are Steiner and Catherine, and it turns out Catherine knows a guy I was at college with, The American is Veejay, a seasoned traveller. I didn’t record the names of the French Canadians – I remember they kept themselves to themselves. We are not allowed to get our backpacks from the bus – they are all strapped on top, and the bus has gone somewhere else to park for the night.

We find a restaurant about 1km down an unlit street. It’s basic, dark and pretty chaotic, lit only by meagre lamps, and full of other foreigners who seem to have a better deal than us and are staying at a “hotel” called the Pamir across the road. We buy renminbi with Pakistani rupees from people travelling in the opposite direction. Back at the dorm, it’s bedlam. The Pakistani guys are chattering 19 to the dozen, and the light keeps going on and off and on again. C & I have our usual bottle of “travel whisky” with us, and we offer our fellow Westerners a tot. Steiner, who’s a doctor, says he reckons that’s a great idea because in the absence of toothbrushes and toothpaste, the liquor will “kill the germs in your mouth.” We take turns at knocking back a shot using the bottle cap – there is nothing else available to drink from. Things eventually quieten down… until the first man starts to snore. Next morning, Veejay reports having to smack a hand that appeared under her bedclothes in the middle of the night.

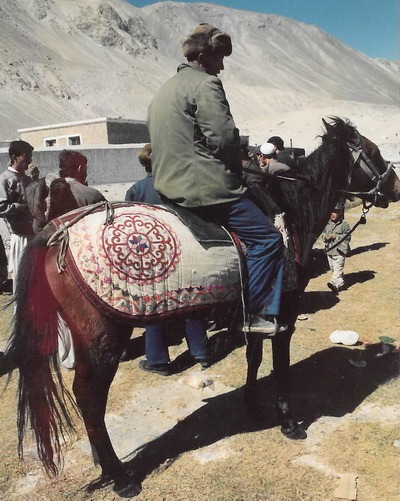

Wednesday 28 September. A long wait to get going. We should have left at 7:00am Xinjiang time, or 9:00am Beijing time to use the official clock. About 90 minutes later we are still standing around in the freezing cold, drinking tea – all that is on offer – and smarting at paying 5 yuan for last night’s accommodation. The bus company has locked our passports in an office and only returns them when we hand over the payment. But the spectacular scenery on the drive north soon takes our minds off the hassles. The sun eventually shines through the windows and warms us up. There are few settlements to see at first. The landscape is barren – reminds me of eastern Turkey but higher and wilder. Skirted two 7,000+m peaks – Kongur at 7,595m and Muztaga at 7,546m – and past lake Kalakuli, and yurts inhabited by nomads. There are a few goat herders, their belongings carried on pack donkey. One man, dressed in a fur hat, long black cloak and black leather boots, sits astride a donkey leading three camels.

We stop for lunch at a kitchen alongside the road, and the space around us turns into a pop-up market as the Pakistanis on our bus meet the local nomads to trade. Our fellow bus passengers are selling waistcoats, coats, macs and jackets – often straight off their own backs. The haggling was intense – it’s big business! And it’s also old business – people living along the old so-called Silk Road, of which the Karakoram Highway is a part, have been doing this for centuries. Many of the older locals are wearing traditional garb like the old chap on the donkey. The women wear voluminous skirts over what look like men’s trousers, with knitted jumpers, jackets and knotted headscarves – red is the predominant colour. Their hair is in two long plaits, often with ornaments of silver-coloured coins and chains woven into the hair. They are interested in the jewellery that we Western women are wearing, and finger our rings, earrings, bracelets and pendants, though none of us are willing to swap them for the coloured glass pieces the women offer in exchange.

Nearer to Kashgar, the mountains recede into the distance, eventually to disappear behind the haze. The land is rocky and sandy, the temperature rises markedly. We see many more people and houses – the latter surrounded by high walls pierced by elaborate double wooden doors. We stop for a snack, probably at Upal, and buy tasty bread rolls, beer (welcome in the dusty heat, not to mention being outside of Islamic Pakistan) and hard-boiled eggs. Tables outside stalls along the road into the city are brimming with grapes, peaches, onions, potatoes, and green and red peppers.

Kashgar deserves its own post – coming soon!. This is the part of the journey that has changed the most. The Chinese have been tearing down the old alleyways and houses, replacing them with modern concrete blocks. The Kashgar we knew is long gone.

The return journey

Tuesday 4 October. The bus is due to leave at 11:10am Xinjiang time, but we stand around waiting for something to happen. We give in our tickets, and stand around some more. Luggage is loaded on the roof, we stand by the locked bus door waiting to get on and grab good seats. We all start shoving our bags through open windows onto desired seats until one Pakistani chap climbs in, at which point the until-now unseen driver materialises from heaven-knows-where and hauls him out amid much shouting.

The weather has got colder in the last couple of days and we are well prepared clothes-wise this time. We’ve bought lots of food – bread, fruit, biscuits, hard-boiled eggs and even some cooked sweet potato that Veejay bought in the bazaar. We’ve also got a couple of bottles of “port” – the nearest we can get to Western wine. We’ve kept our washing gear out this time.

We eventually get on the road. The bus stops at Kalakuli lake, where several of the Western passengers get down. On the way up, I thought it looked rather romantic, with the sunshine sparkling of the turquoise water, but now the sky is low and grey and the yurts are shrouded in fog. Rather them than me. We’ve had some sleet on the way here, and the snowline is much lower than on the way north. We pick up a lone traveller from Hong Kong (my home town at the time), who’d been shivering for three hours by the side of the road waiting for the bus to appear.

It is dark by the time we reach Tashkurgan, the most westerly town in China. Veejay, C and I walk down to the Pamir hotel but it is sometime before any staff materialise. C & I get a room but is has no light in the bathroom, a thin dribble of water from the tap, and the loo doesn’t flush. After much discussion that descends into an argument we eventually get given another room that’s a bit better. At least the bedding is thick and warm and we are cosy. Veejay is in the dorm. We eat at the cafe across the road – kebabs and noodle soup. It’s where we ate in the dark last time – this time the light is on and it doesn’t improve things, now we can see how scruffy and dirty it is! On our return we have difficulty getting the key for our room from the “front-desk clerk” (I use the term loosely), and I’m afraid to say I got into a bit of a shoving match with her to get the key.

Wednesday 5 October. Miracles will never cease – the bus is only half-an-hour late setting off. It is FREEZING, and it’s only early October, What must it be like in January? There’s obviously been a lot of snow in the past couple of days. We reach the customs post at Pirali about 10am and get through pretty quickly. But then we have three hours of standing by the road waiting for the bus – the SAME ONE – to pick us and our luggage up. Luckily as the sun gets higher in the sky it warms us up. We consume what remains of the port, knowing we couldn’t take it into Pakistan anyway.

Up and over the Khunjerab Pass, dazzling in the snow and sun. At the last checkpoint on the Chinese side, a PLA soldier gets on the bus offering to change US dollars into Pakistani rupees – he is armed with thick wads of notes. Private enterprise among communist soldiers! We stay at the comfortable Tourist Lodge in Sust – we get the manager to put an extra bed in a double room so Veejay can share with us – she’s on a very tight budget.

Thursday 6 October. Natco bus to Gilgit. Very crowded, packed with goods belonging to the Pakistani traders. Veejay gets off at Karimabad, as do most of the other Westerners on board. Beginning to regret we decided not to stop, because it looks very pretty. Trees aplenty, cultivated fields, stone houses, roofs piled with harvested crops. But we want to go to Skardu, and are running short of time for two side trips. (It remains a regret to this day that we did not stay at Hunza, but I would not have missed Skardu for the world, either.) We are sorry to say goodbye to Veejay, she was a lot of fun, no airs or graces, and had wonderful stories to tell about travelling around India in the early 1970s. Whatever happened to you, my hippie friend? I hope you enjoyed your life and are still around somewhere regaling people with stories of that crazy trip on the bus up and down the world’s highest road.

Final thoughts

Skardu is for another blog another time. From there we flew (with our hearts in our mouths as the big jet darts between towering peaks) to Islamabad and a few days later on to India. The Karakoram Highway was without a doubt the best trip we have ever done, in almost 45 years of travelling together. The scenery is stunning – from the narrow, steep gorges and frothing, tumbling rivers to the open plains, snow-capped mountains, brilliant blue skies and sparkling snow. I think of the characters we met – the marmot man, the manacled prisoner, the Pakistani chap we called tea-cosy because of his knitted hat (and who was always the very last on the bus and held us up a few times, but we were all on laughing terms by the end of the trip and shook hands as a goodbye).

I loved seeing the lifestyles of the peoples whose home lands we passed through. Little children waving to us as our bus trundled through their settlement; people out in the fields; herders of sheep, goats and yaks; ruddy faced, laughing Tajik women. And not forgetting our fellow travellers: the Pakistani traders who were unfailingly resilient and always ready for a laugh and dance. And of course the young Han Chinese soldiers posted to a very distant corner of their country who found us Westerners almost more bewildering than they did the Uyghar and the Tajik locals.

The bad? Not much, really. There were instances that got us mad or frustrated at the time, but it didn’t take long for these to turn into great travel stories that we laugh at. There was the unforgettable night in the dorm with 30-plus Pakistanis and the Fawlty-Towers-like service at the Tashkurgan hotel. We could have done with better cold-weather clothing, but we made do (we soon threw away the furry hats from Kashgar market – they got very smelly). Yes, we got sore bums from sitting for hours and hours on inadequately upholstered bus seats, not to mention rough road surfaces, but the scenery took our minds of it much of the time. Seeing the detritus of a landslip was a stark reminder of the dangers of travelling along the Karakorum Highway. And travelling along narrow sections cut into rock, with a sheer drop on one side into a narrow, rocky river valley had our hearts in our mouths a few times. But the worst part was probably the frustrating waiting for the bus to leave (and this was mainly a problem on the Chinese side). You take the rough with the smooth!